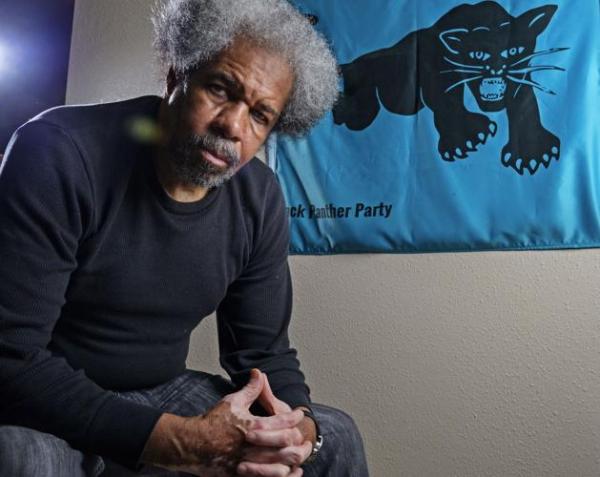

Albert Woodfox. Advocate staff photo by Max Becherer

I thought that my cause, then and now, was noble. So therefore, they could never break me. They might bend me a little bit. They might cause me a lot of pain. They might even take my life. But they will never be able to break me.

Albert Woodfox, 2010 (during his 36th year in solitary confinement)

On August 4, 2022, Albert Woodfox, one of the political prisoners known as the “Angola 3,”1 died as a result of COVID-19. Albert’s family issued this statement:

With heavy hearts, we write to share that our partner, brother, father, grandfather, comrade and friend, Albert Woodfox, passed away this morning. Whether you know him as Fox, Shaka, Cinque, or Albert—he knew you as family. Please know that your care, compassion, friendship, love, and support have sustained Albert, and comforted him.

Even in the long and foul history of America’s oppression of Black people, the deliberate torture and torment of the Angola 3 stands out for its barbarity. Each of them spent decades in solitary confinement in six-by-nine-foot cells, 23 hours a day, subjected to gassing and beating if they raised any complaint. For years they were even denied books, magazines or radios, in a deliberate effort by the authorities to break their spirits and sanity.

Woodfox spent 44 years in solitary. When his mother died in 1994, he was denied permission to attend her funeral, and the same again when his sister died. Prison authorities admitted this entombment was aimed at stamping out or containing the radical political influence of the Angola 3 and the Black Panther Party with which they were affiliated.

Yet what stands out even more sharply is the way in which the men—to use Bob Avakian’s phrase—“rose above the muck and the mire,” above the mere struggle for survival for oneself, above the dog-eat-dog mentality of capitalism, and soared to the heights as selfless fighters against the oppression of Black people and against the oppression and degradation of humanity as a whole.

Albert Woodfox was born in New Orleans on February 19, 1947, and for the most part was raised there. Desperately poor, as a teen Albert stole bread and canned food for his family. When he was 18, petty crimes landed him at the huge Angola prison complex in Louisiana.2 Angola was not just built on the site of an old slave plantation, it operated like one. Black prisoners worked the fields while white prison guards on horses, armed with shotguns, acted as overseers. Any infraction could mean being fed into a network of rape by other prisoners, which was encouraged by the guards.

Woodfox was released after eight months but then rearrested for armed robbery and sentenced to 50 years in prison. He fled to Harlem but was picked up and thrown into the Tombs3—New York City’s own hellhole of incarceration—for over a year.

But in that time his whole life changed! Albert was imprisoned with members of the New York Panther 21, Black Panther leaders and activists who were framed on bogus charges of plotting terrorist attacks (all 21 were acquitted). The Panthers held great authority in the Tombs, not through fear but by treating people with respect and educating them to see the systemic racism of the U.S. capitalist system that had driven people into crime and prison, and that this was part of a broader system of oppression that needed to be gotten rid of. Prisoners were sharply challenged to get with that struggle instead of petty crime.

Woodfox wrote later:

It was as if a light went on in a room inside me that I hadn’t known existed. I had morals, principles and values I never had before. I would never be a criminal again.

Albert took this spirit back to Angola. He hooked up with Herman Wallace (later joined by Robert King) to form a Black Panther chapter there. One of the first things they did was to insist on an end to sexual violence among the prisoners. They fought for reading matter, for decent food, and other improvements. They used the Panthers’ 10-Point Program as a guide both for study and for action, and worked to stay connected to the radical movements nationally.

And Woodfox also immersed himself in the study of radical and revolutionary thinkers, from George Jackson and Frantz Fanon to communist leaders Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong. Albert developed a lifelong discipline of getting up in the quiet of 3 a.m. to read for two hours each day.

Woodfox commented that his attitude towards people changed as he took on this role, which gave him the strength to fight on:

You know, throughout all this, I developed an unbelievable love for humanity and dedicated myself to doing whatever I can to better humanity.… And I thought what we were doing was a noble cause. So we were prepared. And so the beatings and the gassings and the decades of solitary confinement, you know, was really—although painful and difficult, it never got to the point where they were able to break us.

Albert was free from prison for only six years of his entire adult life, but used even those few precious years to continue fighting against injustice and struggling to understand the world better. His example—and that of all the Angola 3—needs to be honored, celebrated, and most important, built on. The potential for thousands and millions who are today caught up in all kinds of negative bullshit to make the leap to becoming emancipators of humanity is the hope and future of humanity, a challenge to all that we have to fight for fiercely, especially in this time when the possibility of revolution grows greater.

Six Degrees of Separation: Reflection from a Revcom Staffer

The tribute to Alfred Woodfox is very moving and inspiring. I have a six-degrees-of-separation connection. In the fall and winter of 1969, I did my internship with a prison reform organization working full time going cell-to-cell in The Tombs interviewing prisoners for eligibility for "pre-trial diversion" in that "modern-day" slave prison where the Black Panther Party 21 were on trial. I met them there—they recruited me to read and distribute their paper, and that was my first serious encounter with revolutionaries. They and the reality I encountered convinced me to give up on reforming the system, and they encouraged me when I went back to college to start a BPP solidarity committee (there was one already which I joined)... and that set me on a winding path that took me to the Red Papers and Bob Avakian...