It was with shock and sadness that I learned of the death of Dr. Paul Farmer at his hospital in Butaro, Rwanda. Only 62 years old at the time of his death, Paul, a specialist in infectious diseases, had a passionate commitment to providing quality health care—with dignity and respect—to the poorest and most underserved people in the world, and to using his training as a doctor and medical anthropologist to identify and address underlying causes giving rise to the chronic illnesses he was confronting among his patients—from HIV to tuberculosis.

Paul Farmer is best known for co-founding the nonprofit organization Partners in Health (PIH) in 1987. The initial mission of PIH focused on providing health care to the underserved rural residents of the central highland region of Haiti, where he had volunteered after medical school. These are among the poorest people—in the poorest country—in the Western Hemisphere.

I got to know Paul soon after PIH was founded. One of his first books, The Uses of Haiti, was one of the few—at the time—that went into the real history of the people of Haiti, and how they had been brutalized and oppressed, by centuries of colonialism and the overall system of capitalism-imperialism. It especially and scathingly exposed the horrific historic role of the United States in keeping Haiti downpressed. The book was very popular at Revolution Books in Cambridge, MA.1

Paul would stop in from time to time, to see how his books were doing and chat. He said that coming to the store helped keep him “grounded.” Our conversations were rooted in a mutual desire of acting in the interests of humanity.

This desire to act in the interest of the people also led Paul to be a vocal advocate for training people from the local communities to be health care professionals. While PIH went on to set up clinics in a dozen different countries, one of his proudest accomplishments was the opening of a PIH-initiated teaching hospital in Mirebalais, Haiti.

Paul would always return to the fact that he felt a compelling responsibility to provide health care to people who others—and the system—had abandoned. Because of that, many of the PIH clinics were established in the most desperate of communities, and often, some of the most dangerous.

Paul Farmer and patient at teaching hospital in Mirebalais Hospital, Cange, Haiti, 2013. Photo: Wikipedia

In the early 1990s the PIH clinic that had been set up in Lima, Peru, during the brutal dictatorship of U.S. puppet, Alberto Fujimori, was attacked by Maoist revolutionaries with the Communist Party of Peru, commonly referred to as the “Sendero Luminoso” (Shining Path).2 He—rightfully, in my opinion—condemned the attack but refused to join the chorus of voices slandering and demonizing the revolutionary People’s War. He said that even though he thought they were wrong, he could understand how the revolutionaries may see the clinic as an extension of the U.S.-backed Fujimori regime that needed be targeted.

Unfortunately, over time, Farmer’s somewhat single-minded—and ever more narrowing—focus on developing locally-based health care led him to increasingly lose sight of how the overarching dynamics of the capitalist-imperialist system were shaping his decisions, leading to associations and compromises that ran counter to the larger interests of humanity, some of which were downright harmful. For example, in 2005, PIH accepted an invitation to develop a healthcare program in Rwanda (a small country in central Africa closely aligned with Western imperialism). Rwanda was only years removed from a genocidal civil war, and the U.S.-backed regime that came to power, and its leader, Paul Kagame, were deeply implicated in the horrific crimes of that war. In 2010, Paul accepted the position of deputy special envoy from the United Nations to Haiti under the special envoy (and former U.S. president) Bill Clinton, after the devastating 2010 earthquake. The U.S. and the UN’s role there ended up only adding to and intensifying the long-term suffering of the Haitian people. These were bad—and harmful—decisions and acts.

By this time, I had lost touch with Paul. On learning of his death, in reflecting on the overall arc of his life, including these harmful acts, I thought of these words from Bob Avakian, BA, from a speech several years ago:

… Look, I have enormous respect for the people who go become part of Doctors Without Borders. But there's a tremendous burnout rate among these people, too. The problems are so enormous and grow at such exponential dimensions while they're trying to do something. Because people haven't wrenched themselves free of the imperialist system and established a proletarian state power. And this suffering will go on and on and get worse until that is what happens. When you see this and understand it—not refracted through a bourgeois or revisionist prism, but when you see it from a communist standpoint—it leaps out at you: the crying and urgent need for proletarian revolution and proletarian state power. Yes, this revolution has to go through different phases. But in essence, and in the final analysis and fundamentally, proletarian revolution and proletarian state power is what it must be aiming for, as the first great leap toward the final goal of a communist world.” [Emphasis added.]

- From "Views on Socialism and Communism: A RADICALLY NEW KIND OF STATE, A RADICALLY DIFFERENT AND FAR GREATER VISION OF FREEDOM" by Bob Avakian, March 8, 2006 [emphasis mine]

What I appreciated about Paul were not only his medical accomplishments (many of which were quite remarkable), but how his decency and his own love and respect for the basic people—all around the world, including the “least among us”—continued to bubble through. But without an understanding of the need for “the first great leap”—the revolutionary seizure of state power—that motivation, that love no matter how genuine, how deep, will always and necessarily run up against the killing constraints and dynamics of the capitalist-imperialist system. We need a revolution to overthrow this system—nothing less!

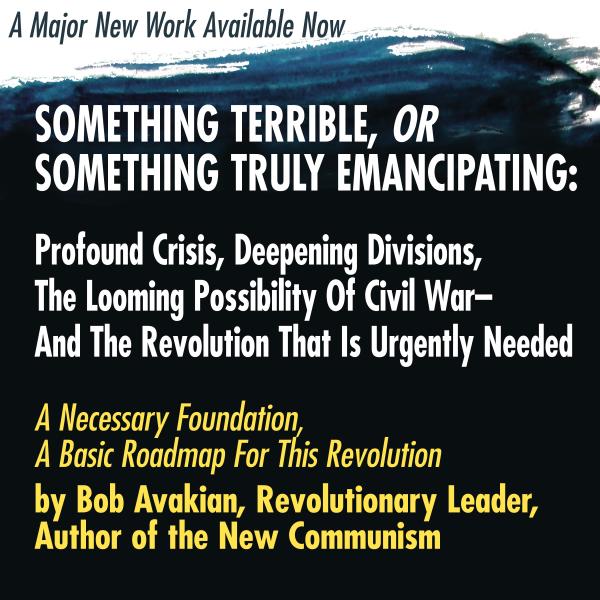

We are now living in a rare time in history where this revolution is possible. To realize this and to do so with BA—and the foundation and framework of the new communism he has developed—is a truly remarkable opportunity. I am convinced there are many potential Paul Farmers in the world—of all generations! We need to reach them, bringing this truly emancipating possibility—and fight for this!