We proceeded systematically, village by village, and we destroyed the houses, filled up the wells, blew down the towers, cut down the great shady trees, burned the crops and broke the reservoirs in punitive devastation. So long as the villages were in the plain, that was quite easy. The tribesmen sat on the mountains and sullenly watched the destruction of their homes and means of livelihood.... At the end of a fortnight [two weeks] the valley was a desert, and honor was satisfied.

—Winston Churchill, recounting a “punitive” raid in India, quoted in Legacy of Violence

Caroline Elkins is a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and founding director of Harvard's Center for African Studies. She spent ten years, traveling to four continents, researching and writing Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire. This is a highly important and timely study of the history, the workings and horrors, and the ideological justifications of the British empire.

Legacy of Violence is a work of immense and meticulous scholarship coming from someone who has not only sought unvarnished historical truth but also put that truth in the service of social justice. Elkins contributed, as expert witness, to the years-long battle for restitution from the British government waged by survivors of Britain's systematic torture and abuse of detainees during the Mau Mau freedom uprising in Kenya of the 1950s.

Given the importance of this book, I hosted Caroline Elkins for a talk at Revolution Books. Her presentation was followed by discussion involving her, Harvard professor Maya Jasanoff, and myself. People can watch the video here.

Talk at Revolution Books, NYC, by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Caroline Elkins, with her book Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire, joined by Maya Jasanoff, author of The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Globalized World, and Raymond Lotta, writer for revcom.us and a spokesperson for Revolution Books.

I. Introduction: The British Empire in a World System of Imperialism

Legacy of Violence is a forceful unmasking and indictment of the British empire and its genocidal violence. Elkins reveals the largely untold story of mass slaughter and imprisonment; concentration camps; hideous interrogation, rape, and torture; forced migrations and forced labor; terror from the skies; and “take no prisoners” counterinsurgency and more carried out by the British in India, Ireland, Palestine and Iraq, Kenya, Malaya, and elsewhere.

She reconstructs this history of colonial occupation and terror both with rigor and outrage. Reading these accounts, I gasped and then flashed to images of the U.S. military burning villages wholesale in Vietnam, its sadistic torture practices at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, its trained and financed “death squads” in Central America. This is imperialism.

British forces in Malaya burned thousands of bales of rubber, destroyed rubber factories and smashed machinery, before retreating. circa 1942. Photo: Library of Congress

Legacy of Violence analyzes the practice of “systematized violence” (the title of one of its chapters). There is the “everyday” coercion of empire, borne of capitalist-imperialist logic: to exploit and discipline labor in far-flung parts of the world; to extract wealth, from cash crops grown in Ceylonese hillsides to minerals hauled from African mines; to siphon revenues into the British treasury from colonies producing oil, cotton, rubber, tin, cocoa, coffee, and more.

But the violence at the center of this study is the large-scale and extreme violence that moves beyond ordinary laws and policing, that accompanied what she calls “legitimacy crises.” To head off and suppress mutinies, resistance, rebellion, and the danger of revolution in the colonies.

1916, a road blockade in Dublin to halt the British was part of "Easter Rising," resistance that aimed to establish an independent Irish Republic. Photo: Public Domain

And part of the story here is how Great Britain also conscripted its colonial subjects as frontline soldiers, as cannon fodder, in World Wars 1 and 2—for the violent global defense and violent extension of the very empire that subjugated them and denied their humanity.

All in the name of freedom and “civilizing” the world.

Elkins provides a startling statistic: at its height after World War 1, the British empire covered one-quarter of the world's land mass and ruled over 700 million colonial “subjects” (one-third of the world's population at the time). She points out that no empire has rivaled Britain's in global power, domination, and systematic violence. That is, I would add, until the emergence after World War 2 of America's hegemonic global empire, which, unlike Britain's at its colonial height, mainly takes the form of “indirect” rule, of neo-colonialism.

Legacy of Violence focuses on the British empire from the 1800s through the anti-colonial, national independence struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. But this work also stands as a broader and urgent indictment of the blood and bones on which contemporary “liberal-democratic” Western society rests and functions.

It is not possible in the span of this review-essay to do justice to the depth and breadth of Legacy of Violence. I do, however, want to highlight some of its core themes and findings that I believe can help people understand the brutal workings of empire, which is the world of imperialism that envelops us. I hope this stimulates people to dive into the book.

In offering these reflections I also want to put the challenge to people outraged by the suffering on this planet and the destruction to this planet. Learn from this history as part of understanding what has shaped the world we live in and why we need revolution to at long last put an end to empire, to the world system of imperialism and all relations of exploitation and oppression. And learn about and become part of the revolution to bring a radically different and far better world into being.

II. The Legitimizing Ideology of Liberal Imperialism

Elkins begins her study by showing how the British empire was unified by a certain “ideological coherence” rooted in what she calls the “liberal imperial ideal” and the nation's (Britain's) “self-imagination” more broadly. In her Introduction, she identifies a seeming paradox:

Ruling over hundreds of millions of conquered subjects, most of whom were Black or brown, and neither enslaved nor free, presented new challenges. How could Britain justify and maintain its domination of conquered peoples at a time when liberal ideals were rendering its own nation-state increasingly democratic? [p. 10]

My interest resides with the British Empire because it took on a particular configuration that became increasingly violent over time while extolling liberalism's virtues in such a way that it could legitimate episodes of extreme coercion as unfortunate exceptions to modernity's evolutionary triumph. [p. 24]

Legacy of Violence reveals that this is not so much a paradox as a package: “Liberal imperialism endured because reform and repression were both inherent to its idiom and systems.” [Ed. note: "idiom" here referring to the language and distinct characteristics and "style" of liberal imperialism.]

Here is this machinery of violence securing and extending empire. It is an empire crowned by a liberal ideal—against absolutism and old aristocratic bonds, and that wants its subjects to see society as made up of autonomous and rights-bearing individuals.

This “ideal” serves the cause of a “benevolent” and “enlightened” empire: spreading values of virtuous, hard-earned individualism and individual rights... sanctifying private property and the free market as vehicles for realizing the common good... and instituting a project of “developing” and “civilizing” societies of the non-Western world to make them fit for modernity. Elkins points to how 19th century liberal-democratic philosophy explained away colonial domination and subservience:

Universalist ideas gave way to culture and history conditioning human character. Arguments soon emerged over who was capable of embracing notions of rationality and social and economic progress. In an emerging global citizenry, inclusivity would come in stages, if ever. [p. 151]

And she further points to how the “liberal imperial ideal” was completely entwined with notions of racial difference and racial hierarchy.

Savage State-Inflicted Violence Under the Banner of the (Imperialist) “Rule of Law”

In unpacking the ideology and practice of “liberal imperialism,” Elkins highlights the centrality of the “rule of law” in the murderous conduct of empire.

The “rule of law” in British-ruled Palestine translated into mass aerial bombing, terrorist “night squads” and brutal raids, torture by police, detainees caged and forced to drink their own urine to survive—as Britain sought to suppress Arab revolt in the 1930s. This “rule of law” applied in Kenya in the 1950s by the British colonial rulers facilitated the rounding up and detaining of nearly 1.5 million Kikuyu (Bantu people of the highlands of central Kenya) along with other Africans during the Mau Mau guerrilla war—a struggle for land and freedom. Detainees and prisoners were subjected to starvation and forced labor, electric shock, and bottles thrust up body cavities.

1936, Palestinians search through rubble left from British dynamiting their homes in Lydda.

How, one would rightly ask, was this the “rule of law”? How to square the circle of the “sacrosanct” standing of the rule of law in the British liberal tradition, deemed a critical tool against despotism, with the extreme violence of this empire? Elkins coins the descriptor “legalized lawlessness” to answer that:

I use [the term] to describe the incremental legalizing, bureaucratizing, and legitimating of exceptional state-directed violence when ordinary laws proved insufficient for maintaining order and control. [p. 140]

“Legalized lawlessness” involved the lawful declaration of “states of emergency” that gave colonial governments wide-ranging “legal” right to carry out atrocities, and emergency courts the power to detain and execute people, and more. This “legalized lawlessness” was tested and consolidated in Jamaica, India, Ireland, and South Africa—and generalized throughout the empire. Administrators, police officers, military and paramilitary forces, crisply dressed officialdom, spies and operatives—all defending the honor of empire. The imperialist “rule of law” and its emergency declarations conferred “legal impunity” on torturers and interrogators.

Members of a British Army patrol search a captured Mau Mau suspect. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The “rule of law” also engendered its own mechanisms to defuse outrage and protest from radical opponents, and allay social-liberal concern, when atrocities could no longer be denied or hidden. Elkins chronicles parliamentary commissions and panels set up to investigate wrongdoings—with findings typically either ignored or blame placed on “bad apples.” It reminded me of how the U.S. Congress conducted investigations into torture by the CIA in the early years of the “war on terror” following 9/11—but grisly as the revelations were, the Guantánamo torture colony would never be closed.

III. World War Approaches, Liberal Imperial Ideology in Crisis

As mentioned, Legacy of Violence shows how the British imperial mission conjoined coercion with “reform” and “development”: remaking societies through violence to “prepare” them to derive the benefits of a liberal order. But the colonized were, as Elkins has put it, “never there yet,” never quite ready to realize their full humanity. The maintenance and defense of empire—of plunder, control, and exploitation—was rationalized this way. The unjust end required the most savage means. But that “end” was cloaked as an enlightened, civilizing one, while the “means” had the camouflage of legality.

This ideology of liberal beneficence was being contested in a sharpening world situation. In the 1930s, a second inter-imperial world war (World War 2) was approaching. Fascism had consolidated power in significant parts of the world. The British empire would soon be mobilizing subject peoples to fight the “evil” of Nazi fascism and its agenda for empire, as well as that of Japanese imperialism—in essence, calling on the colonized to give their lives to the perpetuation of the horrors of this empire. And while Hitler was obliterating bourgeois democracy and Italy making war on Ethiopia and Japan occupying parts of China... the British were imposing “emergency” regulations in large swaths of the empire to quell resistance and uprising.

1935, Buckley's Riots against Britain: sugarcane cutters organized an island-wide strike against conditions at sugar plantations, St. Kitts, West Indies. Photo: Wikipedia

1935, Ethiopian warriors going to the northern front against fascist Italy during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, November 1935. Photo: Wikipedia

Against this backdrop, a “war of ideas” (the title of a chapter in the book) was raging—revealing strains on and challenges to liberal imperial ideology. From one side, the challenge was coming from intellectuals and writers of colonized and oppressed humanity (many of them influenced by communism) and, in very different register, from fascism.

Elkins discusses how radical Black and Pan-Africanist thinkers from all corners of the empire were exposing and denouncing the hypocritical claims of the dominant liberal discourse:

The repressive glue holding racism, capitalism, and the empire together threw into relief liberal imperialism's moth-eaten promises of redemption at some unspecified future time. From where they sat in time and space, [George] Padmore, [C.L.R.] James, [William] DuBois, [Ralph] Bunche, and others saw little difference between British imperialism and fascism. [p. 303]

Much of this radical “diasporic thought” was centered in London, and Elkins provides helpful background and survey of this important intellectual work.

The British were attempting to occupy the high moral ground against fascism. To many, given that “systematized violence” of empire, British high-mindedness was at best a tattered flag. And, ironically, as Elkins reminds the reader, Hitler himself admired the British empire, quoting from Mein Kampf: “No people has ever with greater brutality better prepared its economic conquests with the sword, and later ruthlessly defended them, than the English nation.” Hitler, it should be noted, also greatly admired, indeed learned from, America's system of legalized racial segregation, documented in the recent study Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law.

But for all this similarity, there was a certain element of difference in liberal imperial ideology, an ideological trope and colonial practice, that mattered in this “war of ideas.” As Elkins puts it:

the [British] civilizing mission had a reformist impulse...[I]n contrast, there was nothing reformist about Nazi imperial ambitions. In Hitler's regime, racial differences were immutable, and the empire was to last in perpetuity. [p. 304]

In other words, Pax Britannica held out the promise of institutional change towards future political sovereignty (self-rule and independence). And the British did implement some social and political reforms in the colonies. This was the case in India, including expansion of education (for upper strata), and increasing degrees of political representation—though strikingly in the case of India, electoral reforms enacted under British rule were also aimed at exacerbating divisions among castes and other social-religious groupings (for instance, creating separate voting blocks for different religious communities).

So there is the iron fist and velvet glove of British colonial rule. Elkins speaks of the absorptive “capaciousness” of liberal imperial ideology. She writes:

Turning its attention to the riots and protests erupting throughout the Caribbean [in the 1930s], the British government's ability to reshape its own discourse to appeal to a wide range of imperial supporters reflected an ideological elasticity that was absent in Nazi fascism. This elasticity was crucial to liberal imperialism's survival. [pp. 305-306]

This is an important insight, especially in light of the continuing adaptability of liberal imperialist ideology, including in its current-day “inclusive” iterations... and the ideological hold that liberal-democratic ideology continues to exert on those seeking social change. It is a point to which I will return at some length in my next installment.

IV. Empire Abroad and Empire at Home

Legacy of Violence illuminates how the forging of empire was bound up with the forging of English national identity, unity, and material comfort—undergirded by the wealth extracted from the colonies.

There is the role of literature, and infamously the Nobel Prize winner Rudyard Kipling: originator of “the white man's burden” and whose writings were imbibed by the British public. There were forms of popular culture, the media, the school system, pronouncements of politicians, creation of “heroes” like “Lawrence of Arabia” (who was in fact a spy and operative of empire). In all manner of ways, the British home population was instructed in the “exceptional” goodness of this empire, unlike other (rival) empires. After all, it was motivated by liberal ideals of individual right and freedom... to conquer peoples and lands.

A side note: Britain in the 20th century had two major ruling-class parties: the Conservative Party and the Labor Party. The Labor Party with its thin veneer of “socialism,” has also played its part in the unifying national project of empire. And the Labor Party was in power during a critical period following World War 2, presiding for several years over a new wave of atrocities in Africa and Asia, presenting themselves, in their own words, as “constructive imperialists” [p. 361].

Taking the measure of the imperial foundations of English society, Elkins quotes from a 1937 essay by George Orwell (no friend of revolution but certainly capable of insight):

Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation—an evil state of affairs.... The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes. [p. 586]

It is an evocative passage. In this connection, the Indian political economist Utsa Patnaik has recently calculated that between 1765 and 1938, England siphoned into its treasury $45 trillion of revenues from India!1

V. The Sickening Adulation of Winston Churchill; The Ugly Truth of Churchill's Devotion to Empire

Winston Churchill is celebrated in Great Britain (and in the U.S.) as a leader and statesman of towering political valor and moral fiber—as a champion of democracy who turned dark times into “finest hours.” The truth is, Winston Churchill was a racist ideologue, practitioner, and defender of empire.

Churchill's role as enforcer and ideologue of empire and his crimes are a thread in several chapters of Legacy of Violence (as well as in Elkins's earlier work, Imperial Reckoning: Britain's Gulag in Kenya). In this limited space, a few of his “shining moments”:

- Churchill helped establish special police “auxiliaries” in Ireland in 1920, recruiting unemployed ex-soldiers from World War 1. They became notorious for terrorizing Ireland's civilian population, and were the model for other such squads that carried out vicious raids to root out resistance in and punish villages and towns in British-controlled territories in the Middle East and Africa.

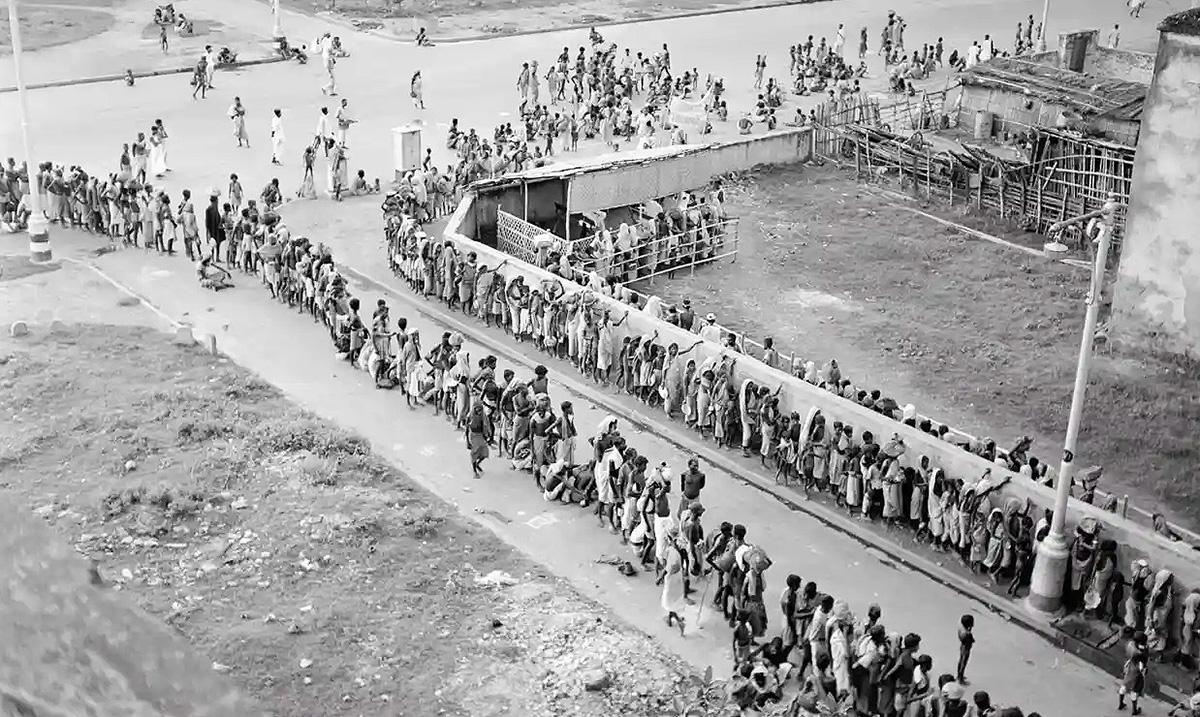

- As India's struggle for independence intensified during World War 2, and with resistance mounting in India to Britain's efforts to secure wartime support and sacrifice, Churchill retaliated. In 1943, he refused to send relief to millions of Bengalis hit by the region's worst famine since the 18th century. Elkins explains that “some 3 million people died due to British wartime requisitioning policies” (with grain diverted, including from the famine-struck region, to the military).

Bengal famine of 1943 took the lives of 3 million people in India. Food scarcity was caused by drought, exacerbated by large-scale exports of food to theaters of war in World War 2 and to Britain. Photo: Bettmann Archives

- Churchill's cabinet in 1954 found ways to circumvent international treaties in order to carry out mass detentions and forced labor in Kenya as part of suppressing the Mau Mau uprising. Perpetrators were granted amnesty.