VI. Britain's Post-World War 2 Attempt to Retake the Global Stage... and the Transition from Direct Colonial Rule to Neocolonialism

Some historical background is necessary. Great Britain came out of World War 2 (1939-45) on the winning imperialist side, along with the U.S. and France—though it was the socialist Soviet Union overwhelmingly responsible for the military defeat of Nazi Germany.

Britain was greatly weakened economically through the war—strapped by enormous debts to the U.S. and a weakened currency (the pound); and it was facing a restive colonized population. The U.S., on the other hand, was spared material damage to its economy and commanded enormous economic and military resources. The U.S. was now maneuvering to establish and assert its political, economic, and financial (and dollar) supremacy—and decisively displace Britain—as the dominant and organizing power in a new imperialist world order. Already, the balance of imperialist power had shifted in the U.S.'s favor in the wake of World War 1.

Elkins illuminates how U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in bringing the U.S. into World War 2 in 1941 had enunciated the so-called Four Freedoms (of speech, of religion, from want, and from fear). The U.S. was positioning itself as “human rights” champion of a new imperial world order. This “rights” discourse was later combined with the moves spearheaded by the U.S. towards establishing the UN with the language of anti-imperial “self-determination” (the right to nationhood). This was directed in large measure at the British and their colonial empire. The call for “universal rights” was a wedge to dismantle and displace the old European-based empires.

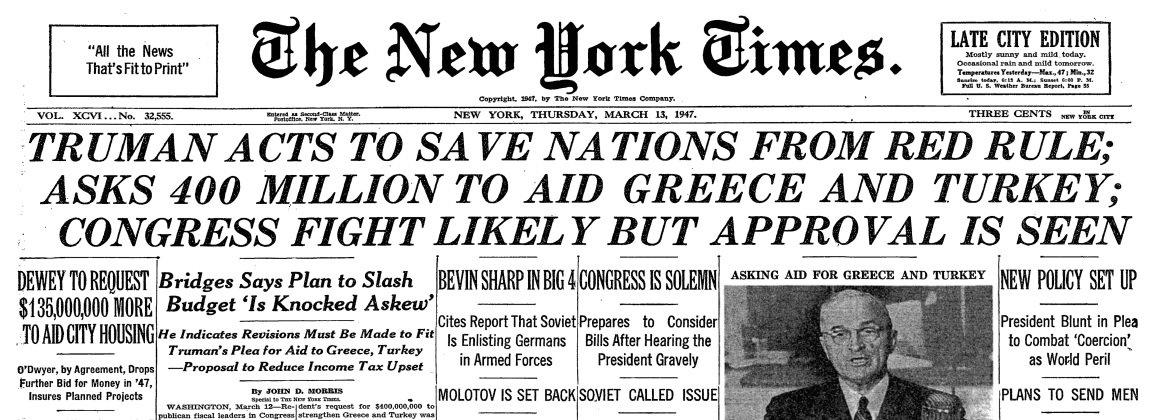

But in the face of the spread of revolutionary movements and the growing influence of communism, and with Mao leading a revolution for national liberation and socialist transformation towards power in China, the U.S. imperialists tacked differently. In 1948, U.S. President Truman announced the anti-communist Truman Doctrine, which provided arms, finance, and training to suppress popular insurgency in Greece and Turkey. As Elkins puts it:

Anti-Communism trumped anti-imperialism [condemnation of the formal colonialism of other great powers], and the United States threw its weight behind bolstering its allies, which included Britain and France, in defense of Western Europe and its need for reconstruction. [p. 372]

Headline announces Truman Doctrine. New York Times, front page headline of March 14, 1947

This Truman Doctrine was the start of the Cold War. One can describe the approach of the U.S. towards its World War 2 imperialist allies as strategically propping up Britain, as part of forging a bloc to confront the then-socialist Soviet Union, and edging out Great Britain (and France) in order to penetrate its colonies.

In 1948, U.S. President Truman announced the anti-communist Truman Doctrine, which provided arms, finance, and training to suppress popular insurgency in Greece. Photo: HS Truman Library

Elkins extensively examines the British side of things and its imperialist calculus. Britain was aiming to re-take its place on the global stage—and doing so on the backs of its colonized peoples. All this was part of a so-called “imperial resurgence.” She describes the outlook of the Labour government in power, and its foreign secretary Ernest Bevin, in the early postwar years:

He and other ministers believed the solution to Britian's financial crisis and immiseration at home, not to mention its increasing dependence on the United States, rested in the oil fields of the Middle East, the rubber plantations of Malaya, and other commodity-producing colonies scattered throughout the world. [p. 373]

And, Elkins goes on to explain that realizing those economic benefits required a new wave of “legalized lawlessness” to “enforce 'civilizing' discipline and push British colonial subjects into labor markets to aid domestic recovery.”

Malaya as Crucial Test and Cruel Proving Ground: 1948-60

Legacy of Violence guides the reader through the horrors of British efforts to maintain their hold in Palestine as the Zionists carried out their savage expulsion of Palestinian Arabs. She chronicles the postwar repression and divide-and-rule policies of the British on the Indian subcontinent—and the “communal cleansing” unleashed by the 1948 Hindu-Muslim partition of the subcontinent and establishment of independent India and Pakistan, with a death toll of some 1 to 2 million people and some 15 million refugees.

Here I want to focus on the book's three chapters concerning Malaya and what the British called the “Malayan emergency” of 1948-60. This was the period following the eventual defeat of the Japanese occupying forces during World War 2 and the reimposition of British colonial rule. It was a time when the British military set out to crush, and eventually succeeded in crushing, a just national liberation struggle in Malaya. I give this section of Legacy of Violence particular emphasis for two reasons: it is a history not often recounted, much less well understood; and because this is a nodal point in the transition from direct to indirect colonial rule as the main form of control in the imperialist world system.

Malaya was rich with exportable raw materials and figured centrally in Britain's post-World War 2 project of “imperial resurgence.” Elkins writes:

Britain wanted political and civil order to facilitate economic control. Most workers across the region, some of whom were demobilized members of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army, survived the war only to inhabit a world riddled with social crises, homelessness, disease, and semistarvation.... To satisfy domestic economic needs, colonial officials sacrificed those of their subjects, while rescuing Malaya's planters and miners to bring crucial dollars from the lucrative rubber and tin industries into the sterling [British monetary] area. [p. 468]

Malaya was, in Elkins's words, the “empire's cash cow,” key to bolstering its post-World War 2 recovery. But there was a big problem. Britain faced a determined communist-led insurgency to break the yoke of British imperialism, and which enjoyed wide support, especially among Malaya's ethnic Chinese who were subjected to vicious discrimination.

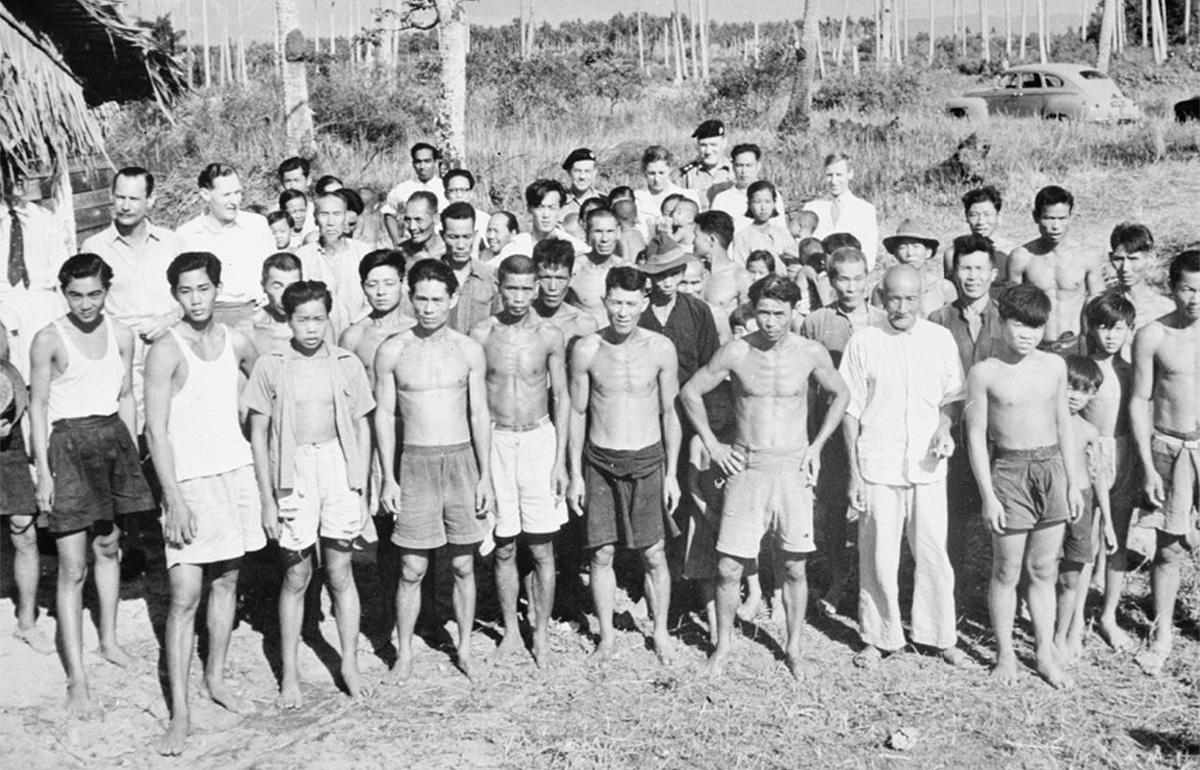

Ethnic Chinese-Malay squatters, forcibly relocated by the British as part of the Briggs' Plan, a counterinsurgency strategy used by Britain. Photo: Malayan Department of Information/Wikipedia

Having locked up some 1.2 million (!) Malayan-Chinese in detention camps, Britain initiated so-called “community development” and “new villages” to win “hearts and minds” (translation: the sadistic iron fist combined with some paltry social programs). Heavily guarded "new village" near Ipoh, Perak. Photo: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies

This became a “battle not only to control crucial imperial resources but also to contain Communism in the early years of the Cold War” [p. 472]—a “danger” magnified by the victory of the Chinese revolution in 1949 (and the support the new revolutionary regime in China began to give to the Malayan liberation struggle).

True to form, Britain imposed draconian “emergency regulations” in Malaya in order to carry out sweeping arrests and mass detentions. 573,000 people, mostly ethnic Chinese, were forcibly relocated into barbed wire resettlements—according to Elkins, this was the greatest forced uprooting of people by British power since the slave trade. [p. 505]

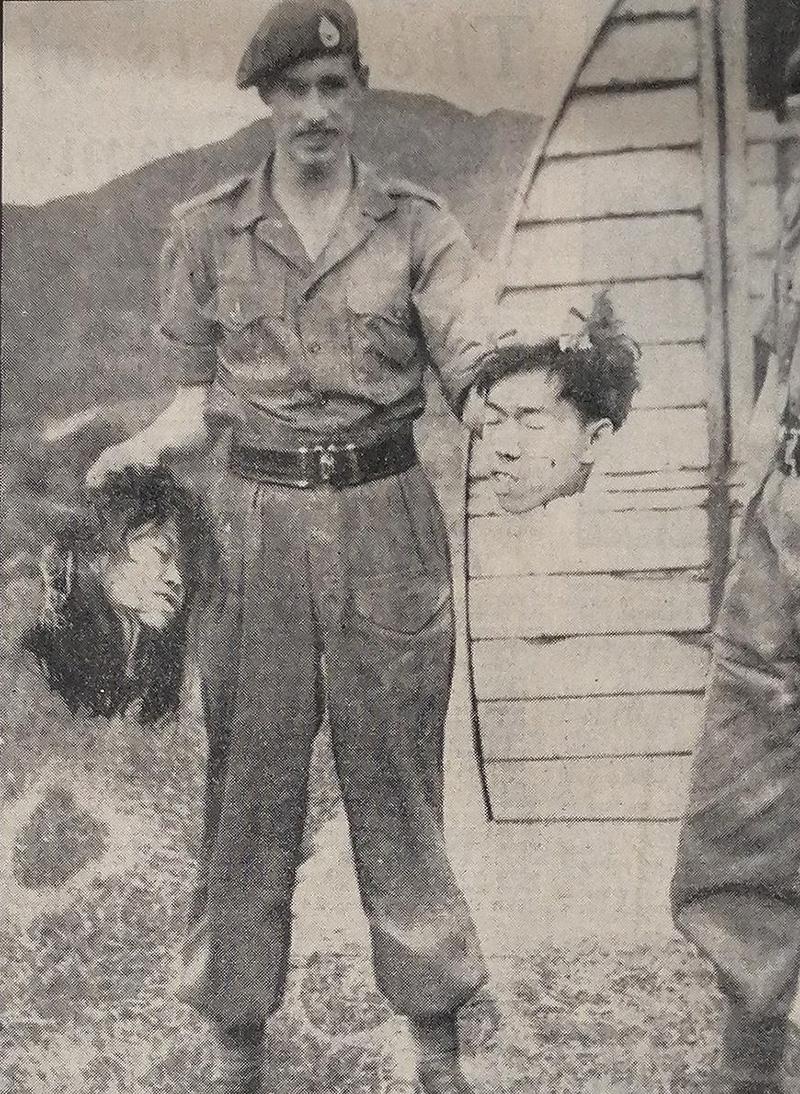

Britain resorted to unremitting savagery in its military campaign. With troops facing difficult jungle terrain and a well-organized insurgency, Britain launched massive bombing campaigns, and used biological-chemical warfare (Agent Orange) in the countryside to wipe out crops sustaining rebel fighters and their peasant supporters. Having locked up some 1.2 million (!) Malayan-Chinese in detention camps, Britain initiated so-called “community development” and “new villages” to win “hearts and minds” (translation: the sadistic iron fist combined with some paltry social programs). A leading architect of the counter-insurgency in Malaya was colonial administrator and military operative Robert Thompson.

Elkins traces the course of this ghastly operation, including its media-propaganda boosterism (along with government measures criminalizing “improper information flow”).

Britain resorted to unremitting savagery in its military campaign to control Malaya. British soldier poses with decapitated heads of Malayans. Photo: Wikmedia Commons

By 1960, the Malayan uprising was firmly crushed. This was also the time that the U.S. was supplanting the French colonialists in Indochina, and beginning to step up its presence in South Vietnam. Robert Thompson's writings on counter-insurgency in Malaya were closely studied by U.S. imperial forces for their covert operations and assassination programs. It would only be a few years before the U.S. scaled up rural counter-insurgency and warfare from the sky to unimaginably genocidal proportions in Vietnam.

From Direct to Indirect Colonial Rule Within the Capitalist-Imperialist World System

On the basis of the massive terror to suppress the guerrilla struggle for national liberation in Malaya, Great Britain “granted” Malaya independence in 1957. This was the transition from direct colonial rule—where imperial control over territories and countries was established through centralized foreign authority run by colonial officials, and in which indigenous populations were denied citizen rights—to indirect colonial rule through formally independent local governments that are still dominated by British imperialism.

In her Introduction to Legacy of Violence, Elkins explicitly states that she is not focusing on the political economy of empire, though she brings this into the picture. Rather, she explains that she is offering a history of the British empire and “how and why exceptional state-directed violence” unfolded across it. But here, in discussing the transition from colonial to neocolonial rule, I want to point to and emphasize that this was taking place within the capitalist-imperialist world system—rooted in and bounded by the capitalist mode of production.

This capitalist-imperialist system operates according to the imperatives of privately controlled production for profit based on the exploitation of wage labor...the pressures of competition compelling continual cost-cheapening and expansion...and rivalry among contending imperial world powers for strategic position and advantage over markets, resources, and regions. A defining feature of the world capitalist-imperialist system is the division of the world between a handful of rich capitalist countries, on the one side, and the impoverished countries of the Third World (or global South), where the great majority of humanity resides and which is a vital source of superprofits—a divide characterized by “lopsidedness” in development as between the oppressor and oppressed countries.

What I am concentrating about this global system of capitalist exploitation (the “economic foundations of empire”) helps us understand why the British imperialists were so intent on holding on to and reconfiguring their empire...and why U.S. imperialism was maneuvering as it was.

The form of neocolonial rule established in the 1950s and 1960s, often in response to independence struggles, pivoted on the recognition of national sovereignty and the resulting establishment of a national government-state system ruled by compliant local elites who acted as guarantors of British interests. Elkins describes a “crony capitalism” that developed in Malaya and elsewhere in which political elites were closely tied to and interwoven with local business interests. These elites profited and grew stronger through contracts for raw materials during the Korean War “boom” of the early 1950s.

In Kenya in 1963, following the horror-filled suppression of the Mau Mau uprising (with methods pioneered in Malaya), the British also embarked on this kind of neocolonial transition.

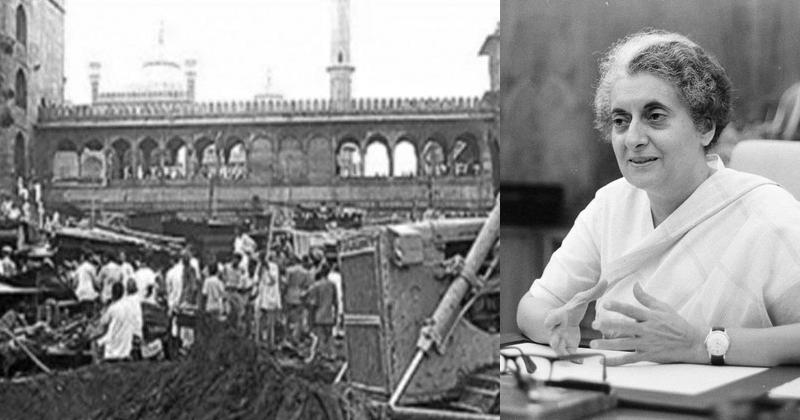

The U.S. often promoted formal “decolonization” in Britain's and France's empires to advance its imperialist agenda—of penetrating these newly independent states and incorporating them into its post-war empire. This was not post-colonialism...but, again, neo-colonialism. Legacy of Violence exposes how many newly independent regimes adapted British law and tradition—including their own declarations of legalized “states of emergency” to quash popular protest and resistance. India, which gained independence in 1947, is a striking example, using this measure for example during 1975-1977 to suspend civil liberties and basic rights, cancel elections, etc.

Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in 1975 due to economic crises and political unrest in parts of India. During the state of emergency she ordered the bulldozing of Turkman Gate, a slum area of Delhi, as part of an “urban renewal” program slated to remove 70,000 people from slums in Delhi. Police shot and killed at least 20 people who protested against the demolitions of their houses.

VII. Comment on a Criticism of the Treatment of Liberal Ideology in Legacy of Violence

Elkins's work on the British empire has, for rather obvious reasons, come under attack by conservative apologists for British colonial rule. But criticisms have also been raised by some “progressive” writers.

For instance, Sunil Khilnani in a review of Legacy of Violence in The New Yorker criticizes Elkins for not acknowledging that while “liberal thought has been a resource for repression,” it has also been a “resource [for] resistance.”

It is certainly true that liberal-democratic principles have inspired fierce anti-colonial resistance and have been an aspirational goal of freedom struggles in the British empire. And most independence leaders fighting British rule in the Third World took up and amplified liberal-democratic thought, demanding that its tenets of right and freedom be applied consistently in the colonies. People like Gandhi and Nehru in India were prominent examples. The language and perspectives of bourgeois-democratic thought were also taken up by anti-colonial leaders in Britain's African colonies—and also in the French empire, going back to the leaders of the Haitian revolution who took up and sought to radicalize the banner of the French revolution.

No True Liberation Within the Confines of Imperialism and Liberal Democracy

But where does resistance lead if it is ideologically encased within the strictures of the bourgeois-democratic framework of the property-bearing individual, with its masking of class domination and capitalist exploitation by formal democratic rights? What kind of societies and economies have been established, in the countries of Africa and Asia that achieved formal independence after World War 2 but remained locked within the liberal imperialist world order?

Just to scratch the surface, we see superexploitation by foreign capital and widespread marginalization; grotestque concentrations of wealth; extreme social inequality, especially the subjugation of women in myriad forms, whether forcibly veiled or driven into the “sex industry”; persistent food crises; chaotic urbanization; and repressive rule. These features of “development” are an expression of that “lopsidedness” in the world between the oppressor and oppressed countries.

India is branded as the “world's largest democracy.” It is a site of unrelieved caste oppression; a society where rape is rampant; with an economy in which the top 10 percent of the rich control over 75 percent of the national wealth; a country whose forests and waters and air have been plundered and degraded in the name of growth, with rural populations displaced by capitalist-led development. [See Oxfam International, India: Extreme Inequality in Numbers, updated September 8, 2022.]

All this poses the question of what is scientifically required—the kind of struggle guided by what outlook and vision towards what goal—for humanity to free itself from the yoke of exploitation and oppresson, and the very division of human society into classes. It is the question of real revolution, of achieving what Marx called the “two most radical ruptures”: with traditional property relations and with traditional ideas. And that goes far beyond, is a radical break with, liberal democracy.

The Liberatory Counter-Example of the Chinese Revolution, 1949-76

In this regard, the very different and incredibly liberatory experience of revolutionary China, when it was socialist in the years 1949-76, stands out.

The historical truth is that Mao led tens and hundreds of millions in a monumental revolution that shattered the domination of imperialism over China and broke the back of the oppressive landlord system and foreign-controlled capitalism. This was a revolution that was transforming society and thinking.

People studying"big character posters" during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution in China; Main forms of struggle in the Cultural Revolution included mass debate (over policy and the direction of society) in public forums, newspapers, and wall-posters; and mass political mobilization.

In China's countryside, the revolution proceeded from land reform to the formation of people's communes that socialized economic activity, combined industry with agriculture, brought women out of the household into the swirl of social and economic change.

Peasants study Mao Red Book, during revolutionary China.

The Maoist revolution ushered in innovations in socialist planning that involved people in the management and transformation of the economy, that consciously aimed to break down divides between countryside and city, between regions, and those who labor mainly with their hands and those who mainly work in the realm of administration and ideas. And, no, China's economy was not a basket case but achieved balanced growth—and living standards rose without the polarization of society into rich and poor. Women were empowered to “hold up half the sky.” The principle of “serve the people” was a motive force for and measure of social progress.

In revolutionary China, Red Guards take the Red Book of Mao's quotations to a factory, January 1967. Photo: AP

China under Mao, especially through the Cultural Revolution, developed the most egalitarian, needs-based health care system in the world. Economists Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen calculated that if India had had the equivalent of China's health care system under Mao, almost 4 million fewer people would have died each year in India. [Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen, Hunger and Public Action (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), p. 214]

Now this experience is vilified and slandered by anticommunist ideologues and defenders of capitalism and imperialism—spewing lie after lie, attempting to frighten people with fabricated (and incessantly rising) death tolls of the Great Leap Forward, tales of fanatical persecution of intellectuals and artists during the Cultural Revolution. It is the trope of “utopia turned totalitarian tryanny”... ”don't go there”... ”long live the capitalist-imperialist status quo.” How convenient, but how utterly removed from historical truth (imagine if I told you that the U.S. Civil War was a bloodbath cooked up by the vengeful Lincoln). And it is a sad commentary on the state of intellectual life that so many intellectuals who are quite critical-minded when it comes to other spheres of reality and episodes of history unthinkingly buy into this nonsense.

I have researched and written extensively on this experience—and provided evidence-based answers to these lies. I invite the reader to look at You Don't Know What You Think You Know About the Communist Revolution and the REAL Path to Emancipation: Its History and Our Future, Interview with Raymond Lotta.

In 1976, following Mao's death, the revolution in China was overthrown by forces within the Communist Party who had fought for a capitalist road of development in a socialist guise. Mao had identified these “capitalist roaders” as a new bourgeoisie under socialism. China today is a fully capitalist society, a rising imperialist power ruled by a capitalist ruling class that still calls itself “socialist.”

Bob Avakian has analyzed why this counter-revolution happened, and the breakthroughs and the problems of the Chinese revolution. In critically analyzing communist theory and practice since the time of Marx, including the experience of revolutions and socialist societies in the twentieth century and drawing from other spheres of human endeavor, Avakian has brought forward a whole new framework of human emancipation: the new communism. It is beyond the scope right here to explore this in depth, but the new communism builds on the experience and lessons of the Russian and Chinese revolutions—but also ruptures in significant ways with aspects of the method and approach of these revolutions—and communist theory overall—that stand as obstacles to the emancipation of world humanity.

Some examples highlighted by Avakian of the real shortcomings and methodological problems in socialist China: There was the promulgation in revolutionary China of an “official ideology” (socialism-communism), when in fact people need to consciously be won to communism. While the notion of a “war against intellectuals and artists” is baseless, there was not the necessary atmosphere fostering the kind of intellectual and cultural ferment—and, importantly, dissent, even views opposed to socialism—essential to knowing and changing the world and creating a society and world in which humans can flourish and the imagination soar. There were certain nationalist tendencies on Mao's part—to see the advance of the world revolution through the lens of and defense of socialism in China and its outward extension. Again, it is not the purpose here to explore this in depth, and readers can go to BREAKTHROUGHS: The Historic Breakthrough by Marx, and the Further Breakthrough with the New Communism. A Basic Summary, by Bob Avakian, to learn more about the new communism, and its breakthroughs.

The point is that we must and can, on the basis of the new communism, go much further and do much better in making truly liberatory and transformative revolution in today's world. But the example of revolutionary China remains a vital reference point for what becomes possible through a revolution that breaks out of the bounds and horizons of capitalism-imperialism and begins to chart a radically different future.

Coming Soon: Part 3, the Concluding Installment.